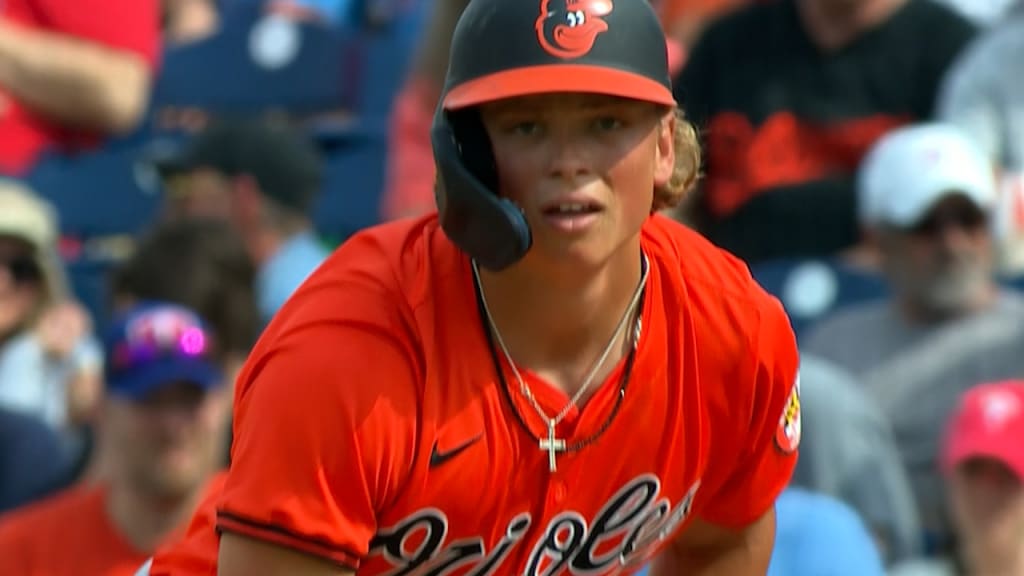

The Baltimore Oriole Who Looks Like a Cherub and Swings the Bat Like a Legend-to-Be

Jackson Holliday has the golden curls and ruddy cheeks of a cherub, but it’s his swing that makes me think of Raphael, the Old Master—such prettiness and mighty grace. Holliday has had that same sweet swing since he was a toddler, and there are videos to prove it. He’s only twenty now, and he still looks like he’s twelve. When the Baltimore Orioles called him up to the major leagues, on April 10th, not even two weeks into the current season and not even two years after he was drafted, fans were already getting impatient. What took them so long?

Holliday grew up inside major-league clubhouses. His father, Matt Holliday, made his big-league début months after Jackson was born, and spent fourteen years in the majors. In 2007, a Times reporter, Tyler Kepner, saw a Colorado Rockies clubhouse attendant throwing batting practice to three-year-old Jackson, and made note of the child’s “perfect” swing mechanics. “Twenty years from now, my money’s on Jackson Holliday,” Kepner wrote. The young Holliday played catch with the great shortstop Troy Tulowitzki and took grounders with Nolan Arenado, one of the best defensive infielders of all time. When his dad played a season with the New York Yankees, Holliday, by then thirteen years old, befriended the slugger Aaron Judge.

As a high schooler, in Stillwater, Oklahoma, Holliday, who’d become a shortstop, was the top prospect in the country, and, in 2022, the Orioles chose him with the first pick in the draft. He announced his ambition to make it to the majors within two years, and immediately established himself as the top prospect in the minors. This past March, after he had a torrid spring training, many fans and analysts expected the Orioles, a team that won more than a hundred games last season, to put him on the Opening Day roster. Instead, he was assigned to Triple-A. The Orioles’ general manager, Mike Elias, said he wanted Holliday to see more high-level left-handed pitching. As a minor leaguer, Holliday had yet to hit a home run off a lefty. So he headed back to the minors, and did so on the first pitch he saw.

After the Orioles called him up to the majors, during a road trip in Boston to face the Red Sox, the team announced that he’d be wearing No. 7. That was his dad’s old number, but it had also been worn by Cal Ripken, Sr., who spent more than thirty years with the Orioles, and whose sons, Cal, Jr., and Billy, had also played for the team. Ripken was the embodiment of the so-called Oriole Way; his number had been unofficially retired since his son Billy wore it. The message was clear: Holliday was the heir apparent to Orioles’ royalty.

He took the field to fanfare. The game, which was aired on the MLB Network, drew the second-largest regular-season audience in the network’s fifteen-year history, surpassed only by Derek Jeter’s final home game with the Yankees. Holliday, who was playing second base, had his first at-bat in the third inning, at Fenway Park, with a runner on first and one out. His father, grandfather, and two siblings sat in a row next to the visitor’s dugout, almost awkwardly close. The first pitch was a welcome-to-the-big-leagues brushback, way inside. A hard swing at a splitter nearly screwed him to his knees. He struck out, and then struck out a second time to end the seventh, finishing 0–4 at the plate. But the Orioles came from behind late to win the game, and the mood was exalted; everyone knows that rookies will struggle.

The next night, he struck out swinging twice more, on the way to another 0–4 finish. In his third game, he struck out all three times he came to bat. “I think I just need to relax a little bit,” he said afterward. On a Sunday afternoon, playing the Milwaukee Brewers, at Camden Yards, in Baltimore, he struck out twice more, but then hit a single. His father, in the front row, stood and cheered. Close by, Cal Ripken, Jr., high-fived Holliday’s wife, Chloe. He’d scored the go-ahead run: perhaps the pressure was off! Then he went hitless in his next three games, striking out another five times. So far, he has one hit in twenty-five plate appearances, and a miserable fourteen-to-one strikeout-to-walk ratio. In the minors, he was known for his plate discipline.

He’s been frozen by changeups and tricked by curves, but usually he strikes out swinging. He’s swung at fastballs, sliders, and cutters, at pitches inside the zone and out. And not one of those strikes was surprising. Hitting a baseball is among the most difficult skills in all of sports. Batters have about two-tenths of a second to decide whether to swing; the muscles in a human eye don’t work quickly enough to track the fastest fastballs. Batters talk about recognizing spins by the patterns of seams on the ball—the railroad tracks of a two-seam fastball, the red spot of a slider. But the seams seem to blur when the confidence goes.

In 2022, Holliday’s teammate Gunnar Henderson launched his career with a home run blasted with such force that his helmet flew off. Henderson hit poorly in his next three hundred plate appearances. He still went on to win Rookie of the Year. Another Oriole, Colton Cowser, who this season is off to the hottest start on the team, hit .115 in his début stint last season. When Cal Ripken, Jr., talked to reporters about what it meant to his family to have Holliday wear his father’s old number, he reminisced about starting his career with three hits in his first thirty-two at-bats. No one else remembers those numbers.

Among the advantages afforded to Holliday—along with good genes, exposure to élite levels of effort and training, access to professional facilities, and peerless instruction—is that he grew up watching his father fail far more often than he succeeded, even when he was among the best hitters in the world. Every big leaguer knows that the difference between a strike and a hit is as thin as grass; all of them can cope with that cruel margin for error, or they wouldn’t have made it as far as they have. That lesson, so out of step with common conceptions of competitiveness, seems to come even easier to their children, who have learned it at their feet. It’s one of the reasons second-generation players dot the league. (The player drafted immediately after Jackson Holliday was Druw Jones, the son of the Braves legend Andruw Jones.)

Baseball is a game of accretion, in which the slow averaging of all its activity is of more consequence than any one big event. That’s not how most of us experience sports—especially these days. We remember the particular excitement of a given game: the gaudy strikeouts, the home run’s spectacle; we watch highlights and viral clips. But a rookie’s début bears about the same relevance to his long-term prospects as his performance as a three-year-old does. The fun of it will be watching him grow up. ♦

Leave a Reply